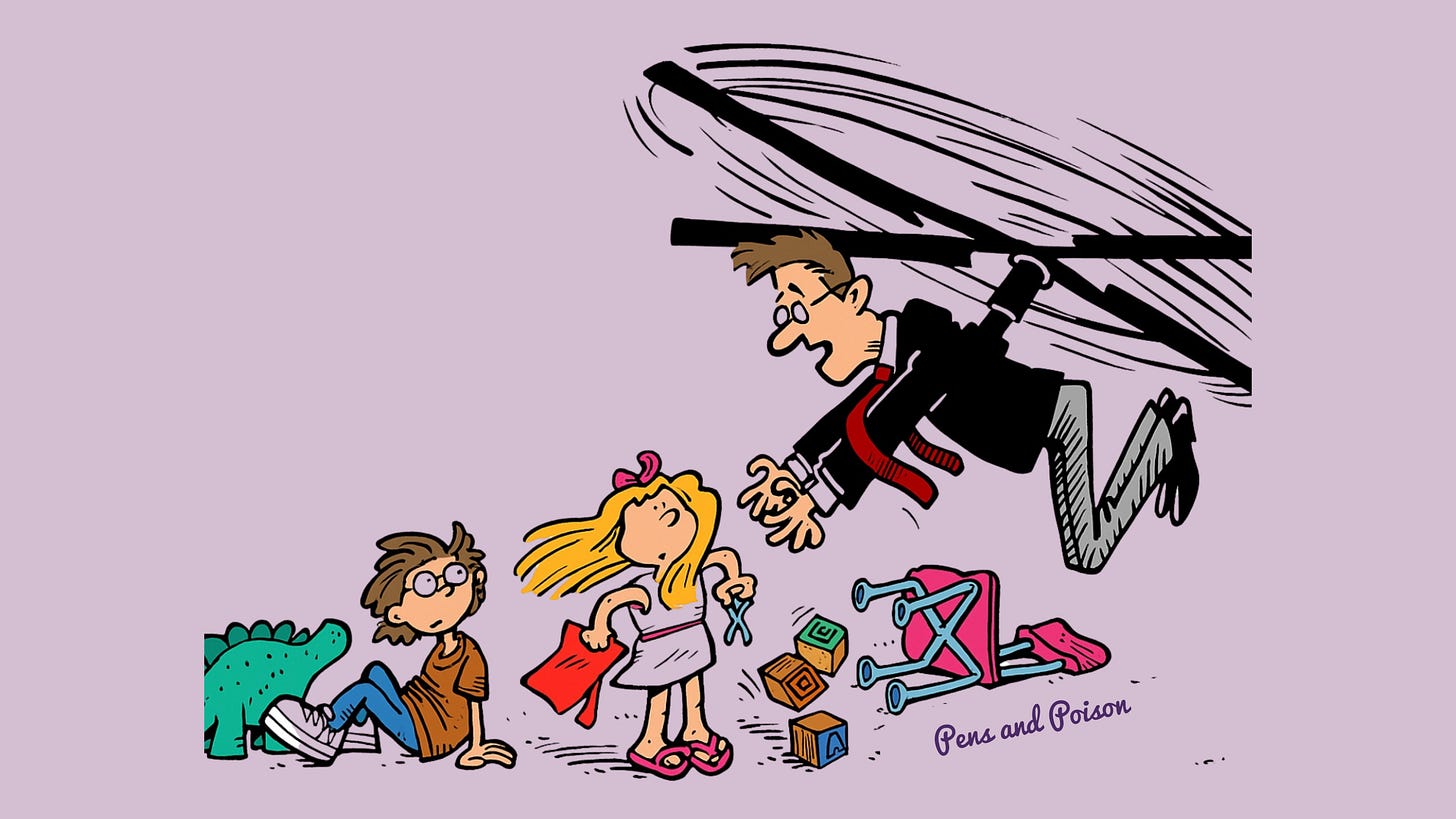

Helicopter Parenting Won’t Get Your Child into Harvard

Overbearing Parents Are Sabotaging Their Kids’ Futures

This essay originally appeared in Minding the Campus on November 3rd, 2025.

It’s that time of year again: the college admissions process for American high school seniors, where students race to prepare application essays for a chance to study at many of America’s elite colleges and universities.

As a private college admissions counselor at my firm Invictus Prep, I guide a handful of students through the college application process, and every year, it’s the same schtick: scheduling frequent one-on-one meetings with students, preparing application materials, reviewing essays, and providing high school seniors with the support they need to get through a process that will shape the trajectory of their careers. But while many students are anxious about their futures, it is often not the students’ anxieties that I end up quelling, but those of their parents.

Most students know that they will end up just fine, regardless of the admissions outcome; parents, on the other hand, come to our first meeting replete with worries about their child securing a spot at an Ivy League or other comparable university. These parents bombard me with questions about what it takes to get into a top-tier institution and whether I think their child will be worthy of Harvard, Northwestern, Berkeley, or, at the very least, Purdue.

What these parents don’t know, however, is that by the time they hire me to look at their child’s essays, their admissions outcomes are, for the most part, already determined.

It’s not that I don’t provide value through essay feedback; on the contrary, a good essay can distinguish a Pennsylvania State University admit from a University of Pennsylvania admit. But beyond stellar grades, test scores, and polished writing, elite schools look for one trait that rests squarely in parents’ hands: whether they’ve raised an independent child.

In fact, I can often predict a student’s admissions success simply by observing their parents’ involvement: the more parents step back, the more likely the student is to thrive in the process. Students whose parents micromanage essays, calls, and decisions almost invariably struggle to demonstrate the independence that elite schools prize.

Elite schools like Harvard or Yale admit applicants based not only on academic and extracurricular performance but also on personality. I even like to joke that the college admissions process is a glorified personality test, and in many ways, it certainly is. Independence is crucial for a student who plans to leave home at 18, move halfway across the country, and independently navigate academic and interpersonal challenges. That is why more often than not, applicants who have been tackling their academic and interpersonal journeys largely on their own tend to fare better than applicants whose parents dictate every aspect of their lives—after all, students who create opportunities for themselves rather than waiting around for their parents to guide their decisions are more likely to become tomorrow’s change-makers.

So, when I’m asked, “What does it take to get into the Ivy League?” I gently offer parents one piece of advice: treat your child like an adult. Support them by asking questions about their academic and extracurricular progress, but by no means get involved in their college application process.

Helicopter parents are responsible, perhaps, for molding an entire generation of young adults who not only feel entitled to everything on a silver platter—from high wages for menial labor to social acceptance for delusional or downright dangerous viewpoints—but who are also unable to do anything themselves.

I cannot overstate the difference between students whose parents trust them and never read their essays, and those whose parents attend every Zoom call, edit every word, and track their every move. I speak to the first group as adults, engaging 18-year-olds as I would my peers. Over-parented students, by contrast, are often unable to engage in adult conversations. I find myself addressing them as I would a 12-year-old. They struggle, for example, to express their opinions, form their own beliefs, or act independently. Because their parents answer every question and manage every decision, they often become “cookie-cutter applicants,” students who look strong on paper but lack unique qualities.

My observations thus far are anecdotal, to be sure. But I believe the trend I have witnessed over the past decade of college counseling cannot be accidental.

Indeed, the available literature on the topic of “helicopter parenting” directly supports what I’ve witnessed firsthand: one study reported by PsyPost, for instance, found that students who agreed with statements such as “My parents will help me with any crisis or problem I may encounter” were more likely to also agree with statements such as “I deserve more from life,” leading to a greater sense of entitlement that stunts interpersonal relationships. Another study by the American Psychological Association found that children with helicopter parents are “less able to deal with the challenging demands of growing up,” suggesting that these students may be less equipped to tackle the difficult transition to college, as well as other setbacks they might encounter as they mature into adults. These students are also overwhelmingly more prone to anxiety and depression, which can, in turn, often inhibit future career success.

Helicopter parents are responsible, perhaps, for molding an entire generation of young adults who not only feel entitled to everything on a silver platter—from high wages for menial labor to social acceptance for delusional or downright dangerous viewpoints—but who are also unable to do anything themselves.

A 2022 study by Frontiers in Psychology found that children of helicopter parents routinely suffer in the workforce: having relied on parents to do everything for them for their entire lives, these young professionals “report low levels of general self efficacy and high levels of peer mistrust, alienation, and poor peer communication.” The same study also suggests that “elevated levels of entitlement” coupled with “postmodern thought” lead to limitations in career success, with students focusing entirely on “self-image” rather than on “relationships with others.” It is no surprise, then, that this same over-parented generation—namely, Generation Z—has the highest incidence not only of mental health struggles but also of self-identification with fringe sexualities: 22.3 percent of Generation Z adults now identify as LGBTQ+ compared with 2.3 percent of baby boomers. It is no wonder that, with an increased focus on entitlement and “the self,” Generation Z has been helicopter-parented into an absurd solipsism that reflects a broader societal malaise.

As an educator, I’ve seen firsthand how much easier it is to work with students one-on-one than with an entire family speaking on behalf of a child. Students who grapple with big ideas—especially concepts of identity, community, and values, as they appear in the college essay process—without their parents’ intervention are better equipped to think creatively, write stronger essays, and grow into more interesting human beings. These are the individuals most likely to spark societal change—or at the very least, make for engaging conversationalists at parties. Since college admissions officers are trained to identify applicants whose profiles and essays indicate the greatest potential for future success, they almost always gravitate toward those who have had the most room for creative growth.

Of course, helicopter parenting is almost always motivated by love—or, at the very least, what these parents, likely plagued by demons of their own past, believe to be love—but it overwhelmingly produces anxious, neurotic, and uncertain adults. While I don’t blame parents who act out of a desire to give their children a better future, such “love” can often have the opposite effect. True love is not only kind and gentle; it is also firm and disciplining. False love, by contrast, tends to enable and insulate. Most kids don’t want to be coddled; they want the freedom to figure out life for themselves.

So, if there’s one piece of advice I can give parents, it’s this: stop joining our meetings and stop reading your kids’ essays. The best way to prepare your child for adulthood is to finally let them live it.

Enjoyed this post? You can Buy Me a Coffee so that I’ll be awake for the next one. If you are a starving artist, you can also just follow me on Instagram or “X.”

Want more Liza thoughts? Pre-order my latest poetry collection, Girl Soldier.

I generally agree with your points here. I would like to add a couple of perspectives from my own experience. First, this extends beyond Gen Z, although it has hit them the hardest. I had a student back in the 1990s who was extremely annoying, entitled, and whined about everything. The staff even referred to him as Sean the Whiner. One day when he was complaining about never having been told that X, Y, and Z would be required of him at the University, I went full on Zen-master at him and loudly mocked him in front of the whole room: "Waah! No one told me I would have to THINK FOR MYSELF!" He looked shocked, but most unexpectedly, he actually took the lesson to heart and became a focused and productive student. Not overnight, of course, because long habits take time to wear away. So there were students like this in previous generations, but it wasn't an epidemic, as it is now.

Second, I have observed in my students whose parents are East Asian immigrants, that the parents take a very firm hand in guiding them. Yet these students do not seem nearly as anxious and entitled as their counterparts with American-born parents. I think that this arises from a cultural difference: in many more-traditional Asian societies, the family is the primary unit, not the individual. The student is an extension of the family, and it is this tradition, rather than anxious helicopter-parenting, which accounts for the parents' high level of intervention and involvement.

The key here is anxiety. If the parents are interventionist, but not driven by anxiety, then the students may turn out to be less independent, yes, but they don't have the same psychological problems around identity, self-worth, anxiety, depression, and meaninglessness that I see in other students. I'm speaking in generalities of course; many individuals will have different experiences. But in general, I think that helicopter-parenting in America is driven by the parents' anxiety, and children learn about the world by observing their parents. If their parents are constantly anxious over their child's welfare, constantly stressed over the child's prospects, constantly worried that something bad might happen to their children if they are unsupervised, then what view of the world is the child going to form? It is going to harm them; it is going to reject them; it is dangerous. They are learning the anxiety modeled by their parents. But in students with equally interventionist parents who are driven by cultural norms rather than anxiety, you get a completely different outcome for the child.

I suppose my point is that there are generational and cultural contexts for your post, which broaden its scope without invalidating your basic points.

Sensitive and smart, thank you Liza. The best thing I did before starting University was to hitch by myself around the sunnier parts of Europe for 10 weeks, living on the money I earned as a truck-driver's assistant. It taught me to trust my own judgement. Not that I got everything right, far from it, but I owned my decisions and learnt from the screw-ups.

The worst thing I did? Not taking a gap year. The horizons of those who did were so much broader, especially in the first couple of terms.