Top 10 Books of All Time

What are my top 10 books of all time and why? It’s a difficult question, albeit one I get asked quite often. To please both my interrogators and my indecisive, literary soul, I’ve made a compromise and added an eleventh book to my list (I really couldn't choose just 10).

Here are my top 10 (+1 bonus) books and my fast take on why each of these books matters and what makes them amazing.

10. Middlemarch by George Eliot

As Wikipedia puts it, this is a novel about “The Woman Question.” Middlemarch follows the story of the 19-year-old provincial orphan Dorothea Brooke and her marriage to the scholarly yet still Edward Casuabon. Meanwhile, over in the town, we meet the doctor Tertius Lydgate and follow his own adventures, eventually seeing an overlap between the two as Lydgate comes to tend to Casaubon during his decline. It’s a novel about gender norms and marriage and love, yet a unique take on these themes in that the plot does not center around a need or desire to marry as we might see in a Jane Austen novel.

9. White Noise by Don DeLillo

Flashing forward a hundred years into the future, we get Don DeLillo’s White Noise, which famously addresses the “fear of death” question that is so central to the human experience in the most bizarre way possible. Our protagonist is a “Hitler Studies” professor, a playful jab at American academic institutions. White Noise is a novel about a typical American family who struggles to understand the absurdity of life. The novel’s fragmented structure reflects the fragmented nature of postmodern thought, and its critique of consumerism and media examines the effects of the postmodern era. Themes of existential dread and paranoia also pervade the work, emphasizing the fear of both life and death that characterize the postmodern psyche. It was my personal introduction to postmodernism and made me quite the big DeLillo fan.

8: Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

We have all met a Count Vronsky in our lives. Anna Karenina is Tolstoy’s masterful work of literature on domestic life. At the center of the novel of course lies their affair, but through the character Levin and his eventual marriage to Kitty, we also tackle themes of Christianity and death—two philosophical topics that are hallmarks of Tolstoy’s work.

7. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath

If Middlemarch is about “The Woman Question,” The Bell Jar is about “The Sex Question.” The novel is fraught and autobiographical—much of Plath’s own experience with depression is chronicled in this book through the eyes of Esther Greenwood, a naive college sophomore who finds herself in New York City for an internship. Esther is neither content with nor interested in the work she’s doing at her fashion magazine—her attention wanders, instead, to sex and love as she reminisces on the nature of relationships and death. The Bell Jar is my favorite book written by a woman about what it is like to be a woman in the face of society and men. It also tackles questions of mental health that are still with us today. It’s worth a read!

6. Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

Today, Brideshead Revisited is best known for being an early novel about homosexuality, but the novel is perhaps more principally about Catholicism and the decay of the British nobility. The implied homosexual dynamic between Charles and Sebastian figures in more broadly and relevantly when we consider the Catholic layer, presenting an explanation of why Waugh never allows the relationship to play out or why he breaks it off so early in the novel. Oh, and don’t forget my favorite character—Sebastian’ teddy bear Aloysius.

5. The Unbearable Lightness of Being by Milan Kundera

This is one of the few books by a man that is very self-aware about men. The Unbearable Lightness of Being follows two couples and their disparate relationships. We meet Tomas and Tereza, who are in a polyamorous relationship at Tomas’s instigation. The novel explores human sexual impulses and desires and is set against the backdrop of the 1968 Prague Spring.

4. Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov is such a master of his craft (English was his third language!) that he manages to create beauty with respect to one of the most vile topics known to man. Because of its subject matter, this book gets quite a bad rep from people who haven’t read it, but I don’t know a single person who has read Lolita who still turns their nose up in disgust. It’s a masterful work in literary history and inaugurates Nabokov amongst the ranks of masterful psychologists (and writers, of course).

3. The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

The Sun Also Rises is a novel about a youthful generation charged with class, glamor, and sophistication. This is the Lost Generation, the disillusioned expatriates who search for meaning in post-WWI Europe—for a way to live rather than to simply exist. Yet their grandiosity acts as nothing more than a veneer for their sickness—sickness not as an illness or even as a plea for survivalism but as incapacitation and artificiality. The Lost Generation, through its inauguration of a new dimension of hope, also ushers in a new era of repression, an existence that is living without feeling and expression of feeling. Hemingway’s writing itself acts as a metaphor for this repression: he uses narratorial omission to say what he does not actually mean to say, and while this is a brilliant technique for a novel age of art, it leaves many of his characters pathetic and despondent, living but not living at all, unable to push past the façade of grandeur to express their true desires, unable to live a truly meaningful life. And Lady Brett Ashley is the coolest f*cking character ever invented.

2. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Master and Margarita is a critique of the Soviet Union through a devil who roams the streets of Moscow and a cat named Behemoth (which is actually funnier in Russian because behemoth is also the word for “hippo”). Coming from a Post-Soviet household, I resonate deeply with the novel’s commentary on decaying social norms in the Soviet Union, as well as its satire on Soviet life. The principal theme in the novel is the erosion of traditional Christian morals through the eradication of religion under the Soviet regime; it certainly leaves us with something to think about today as well.

1. The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

This is the deepest novel about the nature of religion and man ever written. I seem to like theological dramas. That must be because religion provides us with a moral framework to ask and answer some of the most important questions known to man. The Brothers K tells the story of three brothers—Alyosha, Dmitri and Ivan—and the investigation of the murder of their father, Fyodor Karamazov. The most profound meditation on the nature of religion occurs halfway through the book in Ivan’s story of The Grand Inquisitor, a tale of religion and free will.

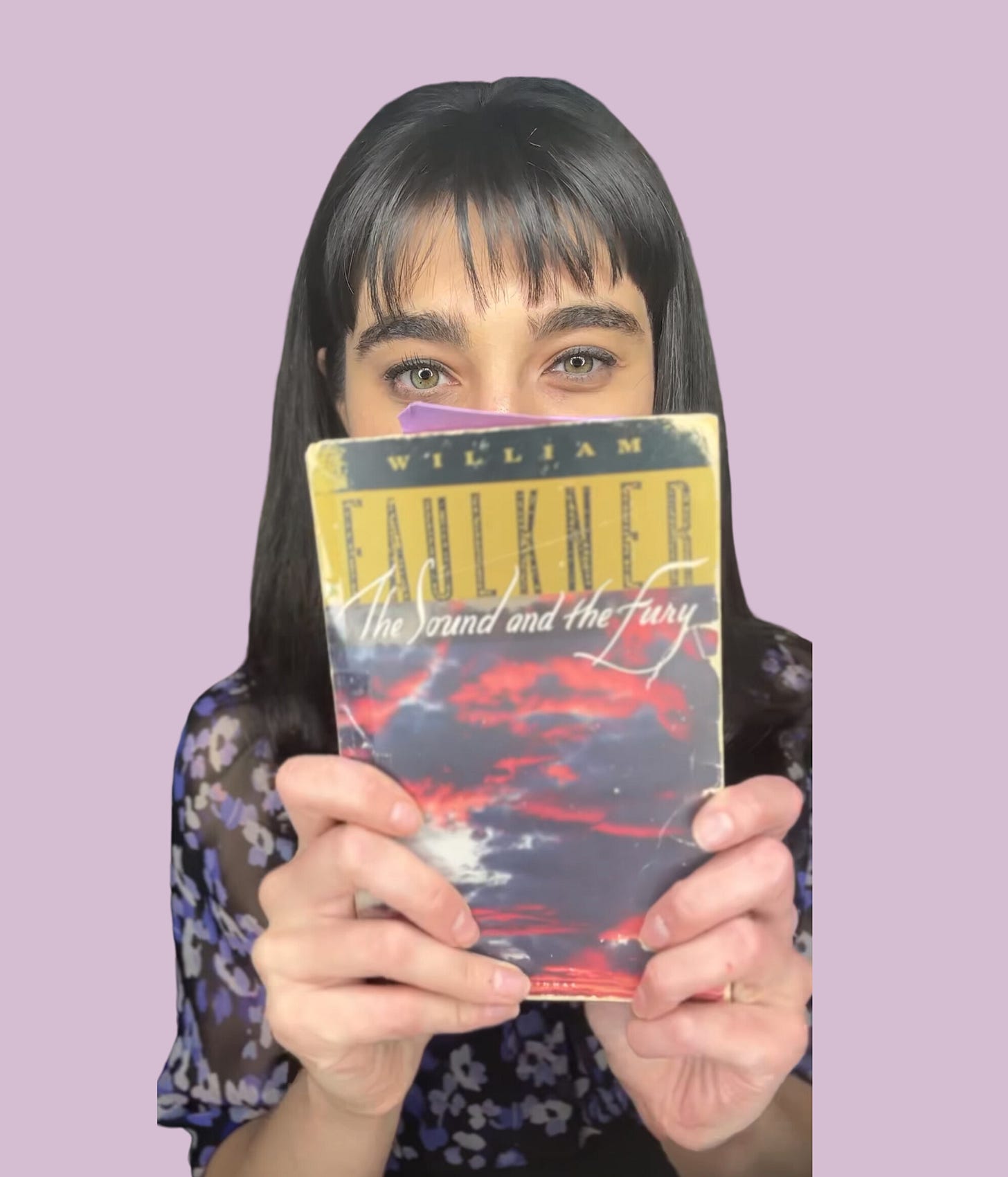

0. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

My all-time favorite book is William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury, which tells the story of the downfall of the Compson family through four different perspectives. My favorite section is by far the second one, which is narrated by the neurotic nineteen-year-old Quentin Compson and establishes Faulkner as a master of human psychology. Quentin, caught up in the ideals of the old South, obsessed with his little sister Caddy, and unable to adjust to his time at Harvard, meets a gloomy demise, but he also appears in one of Faulkner's other monumental works—Absalom, Absalom! The book’s title comes from Macbeth’s famous “Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” monologue and reflects the book’s focus on the absurdity of life.

WOW was it difficult to condense those great books into pithy paragraphs. I hope that piqued your interest. Happy reading!

Master & Margareta is one of my all time faves. Glad it makes another person’s top 10 too.

Great choices!