“Sex-Positivity” Broke Contemporary Literature

Contemporary Literature Can No Longer Speak Honestly About Sex

Last week, I wrote about the plague of soulless writing that has infested the publishing industry. But there’s an equally—if not more—disturbing trend in publishing today, and that is the obsession with “sex-positivity.”

I’m not just talking about the fact that virtually every other book that comes out of mainstream publishing today is nothing more than smut and porn—that’s a related problem that I’ve previously discussed here. I’m talking about the specific propagandistic way that the publishing industry insists on portraying sex—that is, sex must always be “empowering.”

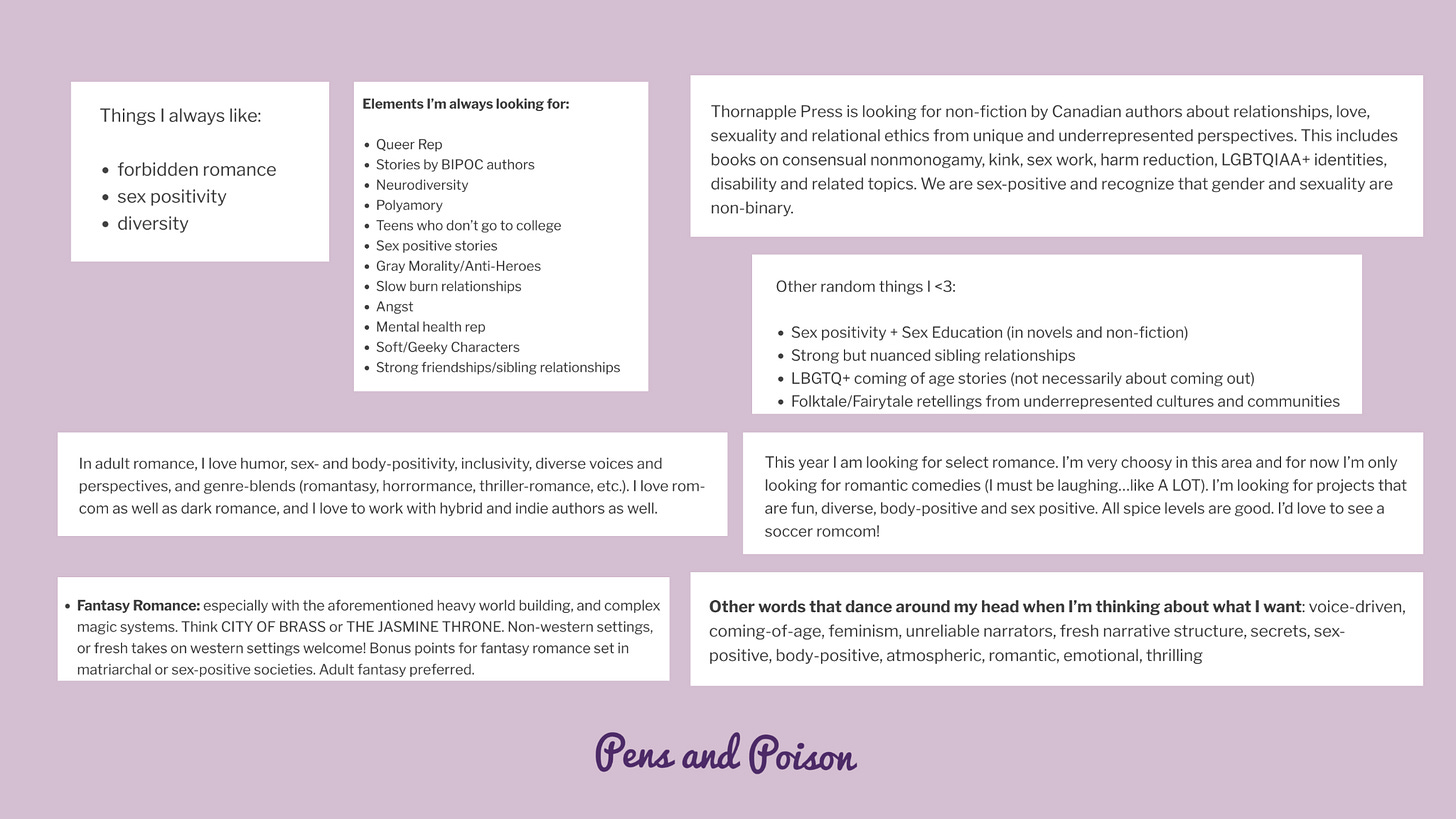

In other words, contemporary literature demands that consensual sex be presented solely in a positive light, where characters “discover” themselves through kinks or other related sexual play as they become more “in tune” with their emotions and identities. Literary agents push this trend to absurdity across all genres, with a search for “sex-positivity” on Manuscript Wish List yielding over twelve pages of results.

And perhaps even more disturbingly, never will you find a work of contemporary literature that dares to question this dominant mentality when it comes to sex; such a book, after all, will never make it past literary agents, who refuse to confront the reality that not all consensual sex is positive by default. In fact, literary agents have developed such an obsession with “empowerment” and “healing” through sex that they will not only shoot down any work of contemporary literature that dares to argue otherwise—they will also be genuinely confused at the mere suggestion that this “do-whatever-you-want” mentality when it comes to sex may actually be both personally and societally destructive.

The plague has gotten so out of hand that even the negative depictions of sex that do slip through the publishing industry are almost always given a positive spin by readers of contemporary literature—even when it comes to portrayals of non-consensual sex. For instance, when writer and Instagrammer Jayden Jelso posted a video this past week decrying the trend of women “discovering themselves” through books that feature graphic depictions of rape, an army of women flocked to his comments section in defense of their perversions, claiming that there is no harm in “consensual fantasy” or that smut is just “literary work with romance in it.” Several comments even went so far as to claim that books depicting graphic sex were helping them heal from their own trauma. What these comments reveal is that the publishing industry has essentially conditioned women to view all sex in a positive light—even when these women are fantasizing about something as violent and disturbing as rape.

In other words, depictions of sex in contemporary literature are almost always delivered with the intention of convincing readers that any sort of sex is healthy by default. There is no harm, many women repeated in Jelso’s comments, of fantasizing about rape so long as no one is physically hurt.

Really?

A 1994 study in Child Abuse & Neglect found that “sexually abused women reported more fantasies of being sexually forced than did women without sexual abuse histories,” suggesting that many of these women getting off to smutty “literature” may be simply putting a band-aid over a more underlying source of trauma. A more recent 2025 study reached the same conclusion, demonstrating that individuals who report frequent coercive or non-consensual sexual fantasies are more likely to report higher levels of psychological distress. While these findings do not amount to a wholesale moral indictment of fantasy itself, they do complicate the publishing industry’s insistence that all sexual expression is not only benign, but actively “healing.”

Why, then, do publishing professionals continue to promote “sex-positivity” as the be-all and end-all? It is abundantly clear, after all, that while sex may of course be uplifting when done in the context of a stable, consensual relationship, not all sex is “positive” or even remotely “empowering.”

I am not a literary agent, so I cannot tell you exactly what is happening on an industry-wide level, but boy, do I have some theories.

The easiest answer is that “sex-positivity” is commercially efficient. If large publishing houses manage to convince the masses that all sex content is positive, then any sort of shame associated with consuming this explicit content becomes a non-issue, thereby driving book sales and legitimizing this industry-wide scheme. Similarly, framing sex in this way removes any sort of liability: sex couched in the language of “empowerment” allows publishers to sell erotic material without having to own up to the harm that it may cause. If smut becomes “identity exploration” and porn is marketed as “romance,” then literary agents and editors are no longer responsible for the psychological effects of the books that make them money.

But there’s a third, more insidious reason that publishing has succumbed to the “sex-positivity” mania: we have created a literary culture that has completely erased all discussions of morality from literature. Simply put, in a literary world that has embraced moral relativism to absurdity, an author who dares to take a stance on the morality of sex commits an egregious faux pas.

I was personally made aware of this phenomenon when working with a literary agent this past year on my novel The Lilac Room.

I have previously discussed my bizarre literary agent “situationship” here, and its demise was no doubt partially driven by fundamental ideological disagreements when it came to the purpose of literature. The most salient of these squabbles was directly related to this plague of “sex-positivity.”

My novel The Lilac Room explores the moral degeneracy of certain members of New York’s upper class. There’s an important ideological development when it comes to sex that forms the core of the book’s moral philosophy. Early in the story, a character named Adam, finding himself in desperate need of money after having gambled away fifty-thousand dollars, convinces his girlfriend Nelli to put on underground sex shows. They raise the money they need through what is, effectively, prostitution (a term that has been replaced today by “sex work” to strip the activity of its moral failures) and gradually enter the seemingly glamorous world of the upper class. Nelli, however, is left psychologically scarred by the experience.

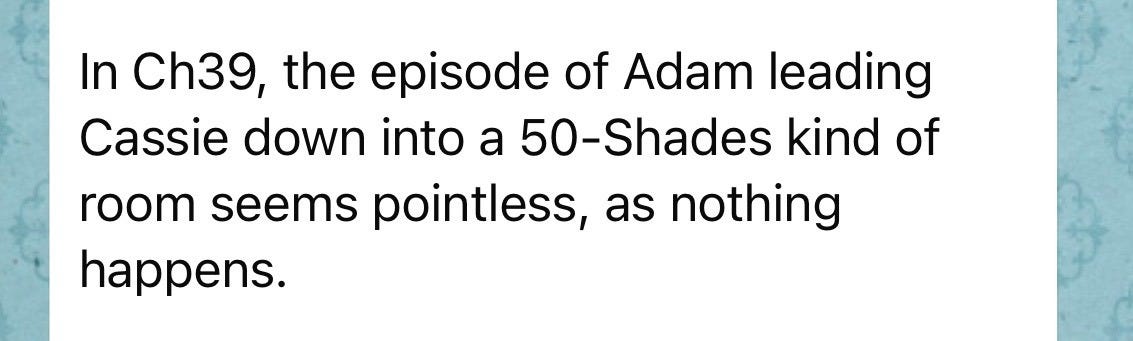

Years later, Adam, still dating Nelli, takes our protagonist Cassie down to the room where he and Nelli used to put on their shows. By then, Cassie and Adam have developed an attraction towards one another, but Adam has learned that “just because something can be done, doesn’t mean it should be done.” Cassie, similarly, values loyalty above all else, and though she is tempted to act on her feelings for Adam, holds herself together out of respect for his relationship. At this stage in the novel, therefore, Cassie and Adam both reach a moment of maturity that demonstrates their moral transformation—and they leave the room without so much as touching one another.

This moment of clarity is one of the most important scenes in the novel because it a) promotes the virtue of loyalty over impulse and b) retrospectively condemns Adam’s previous “sex work.” In other words, Cassie and Adam have now evolved into good people despite their previous sins.

Here’s what my literary agent had to say about all of that:

You can imagine how difficult it was for me to refrain from arguing with him (eventually, I did so anyway).

This literary agent, taught to treat everything as “sex-positivity”—including so-called “sex work” that has left a character permanently scarred—could not even fathom a scene whose whole purpose was sexual restraint rather than empowerment. In so doing, he completely misread the point of the scene because in his ideological world, where all sex work must be positive, scenes that comment on the absence of sex must be superfluous.

My experience adequately demonstrates the predominant mentality that has infested the literary world: there is no room for nuanced commentary on the morality or immorality of certain sexual acts because, to the majority of agents and editors, sex is positive by default, and there is no further discussion to be had.

Frustrated, I had the idea to write a “sex negativity” novel—my most recent novel Blue Snow—which portrays two characters whose sexual fantasy land slowly erodes both of their sanities. It’s probably the most uncomfortable novel I’ve ever written, but there is a conversation to be had about the danger of reducing sex to mere “positivity”—and now is the time to have it.

Because by insisting that all consensual—and sometimes even non-consensual—sex is inherently empowering, contemporary literature simplifies rather than enhances our understanding of human nature. As a result, our literary culture produces characters who are both one-dimensional and fundamentally amoral.

But in a publishing bubble that celebrates minimalist sentences stripped of all human feeling, is that necessarily surprising?

Today, in an industry that has mistaken simplicity for sophistication and ideology for art, we need not only a callback to morality but to literary depth. Because only literature that approaches all facets of the human experience from a nuanced perspective will ever be able to tell the truth about what it means to be human.

Enjoyed this post? You can Buy Me a Coffee so that I’ll be awake for the next one. If you are a starving artist, you can also just follow me on Instagram or “X.”

My most recent novel debuted today. I self-published, and after this, honestly empowering experience, I’m never ever going to query anybody again. I’m positively convinced the industry is cooked, and I’m happy doing my own thing, even if it doesn’t amount to much.

“but boy, do I have some theories.”

I so enjoy seeing sentences like this when you’re diagnosing. I know a +10 evisceration is just moments away.